With the FBI withdrawing its court petition against Apple due to assistance from "an outside party" there is no better time than the present to take a look at the state of the debate on the extent of government surveillance that society should or is willing to accept in the name of security in our mobile first always connected world.

In this instance, the US federal investigative agency was using an ancient clause from the 1700s known as the "All Writs Act" in what some would argue is a dubious manner to compel Apple Inc. to rewrite parts of iOS, that is the iPhone and iPad Operating System (OS). This custom version of the OS would allow the passcode to be entered programmatically thus allowing the FBI or anyone with access to the custom software to brute force crack the code. That is they would try, using a computer, different passcode combinations thousands or even millions of times per second until the correct one is found. Such a mechanism would provide a verifiable way to bypass the security protections designed into the hardware and software of the device. As the passcode also contains the access codes for the key used to encrypt (cipher) the data stored on the phone once known it allows the retrieval of any pictures, videos, text etc saved on the device.

The crux of the US Government argument in this case is that such access is equivalent to that provided under search warrants which are executed through various means including by wiretaps that are provided by telephone companies currently. In effect, forcing Apple to write software to unlock a phone should in the their view be seen as the same as requiring phone companies to tap calls.

At first glance this may appear to be a rather straight forward request especially given the circumstances and individuals, non other than the San Bernardino terrorists, behind the device that the FBI so desperately would like to access. However, when you scratch the surface a little and also draw a few future arrows down the page and look at the implications this is anything but a normal request.

Actually, if it were standard practice for companies to rewrite their software to accommodate law enforcement then there would be no need to dig up and figuratively dust off a 200+ year old act. From this writer's perspective it does appear that some creative interpretations were made to come to this conclusion that such a request could have merit. If this were standard practice then police everywhere could just call up the car makers and lock manufacturers and force them to produce keys to vehicles they have a court warrant to search. Hell, who knows, maybe they do this already and it is just kept secret ;) Even so, this is clearly not common knowledge and doesn't seem to happen does it. So why should we start allowing this now?

Additionally, the wiretap analogy is good but it's not a clear cut comparison of Berries to Berries. In the case of telephone networks the providers actually do have the keys and also certainly on the internal network many of the calls may go over the lines unencrypted as network providers generally only scramble the traffic at the network perimeter. What this means is simply that they (traditional phone operators) are in a position to tap the call whereas Apple has deliberately taken itself out of that position by not storing the keys in the first place.

Therefore, the demand the FBI asks each company is totally different. In the traditional case the statement could be read somewhat like

1 - Please provide me a copy of the data you already have about X and Y at this time and this date

but in this case it would be

2 - We know you don't still have the keys to the lock on data for X and Y. However, since you did sell the door with the lock and didn't keep the original key please go build me a new lock that I can put in that door. This lock needs to allow us to easily copy/create a new key to open the door.

The thing is the first statement is a demand that cannot be refused currently, although companies like Microsoft are challenging even this one by arguing this is only allowed if the organisation's division is the same legal entity and is in the affected jurisdiction and has direct access to the data concerned but should not apply if company or division does not have direct access even if other divisions or departments in the global company have access in another legal jurisdiction. However, the debate on this point is not that the warrant isn't allowed but just about where it has jurisdiction.

But the problem for the FBI is that once the 3rd party, in this case Apple, no longer has the keys and therefore access to the data then the government is essentially asking it to hack its product or in other words create a backdoor. This is something that Tim Cook has pledged not to do as it would be reneging on the commitment to privacy that the company has made to its customers.

Privacy is likely to remain a pillar and a key selling point for Apple as it has always sold its products on security. So long as its business model remains device and customer service driven it is unlikely to need to have deep read access to end user data like other tech companies who have businesses that revolve around and sell access to and ability to predict customer behaviour based primarily on their intimate knowledge gleaned by data gathered from the consumers of their services.

Our business model is very straightforward: We sell great products. We don’t build a profile based on your email content or web browsing habits to sell to advertisers. We don’t “monetize” the information you store on your iPhone or in iCloud. And we don’t read your email or your messages to get information to market to you. Our software and services are designed to make our devices better. Plain and simple.

Tim Cook, CEOApple Inc.

Where this leaves us is in the present situation in which Apple indeed has the right to say no. No, to rewriting or creating products that it does not need or want to create. Until the FBI can find a way to pose the first question it is very likely to find stiff resistance.

Resistance is indeed a good thing. As while law enforcement may deny or refuse to acknowledge the potential correlation between this particular case and future demands or actions. Getting their way this time would invariably lead to further requests in other cases with possibly less just causes. One must remember that these events set precedence not only in the US but in other places as well. Should Apple or any other multinational company concede in the US they will no longer have cover to say that they cannot bend in other territories. Such companies would run the risk of impairing their customers trust, breaching contracts and limiting their business potential. Countries such as China will no doubt be looking on. In fact it is in the best interest ironically of the American businesses and government foreign policy that they do not succeed in this case. As they will be entrenching backdoors going forward in other places where there is far less restriction on the use and nature of government intervention.

Finally, let's also take a moment to remember how this debate started. The conversation was triggered by the shocking revelations of a former Systems Administrator at Booz Allen Hamilton contracted to the NSA, Edward Snowden.

Edward Snowden & Glen Greenwald discussing encryption in Citizenfour

Edward Snowden & Glen Greenwald discussing encryption in Citizenfour

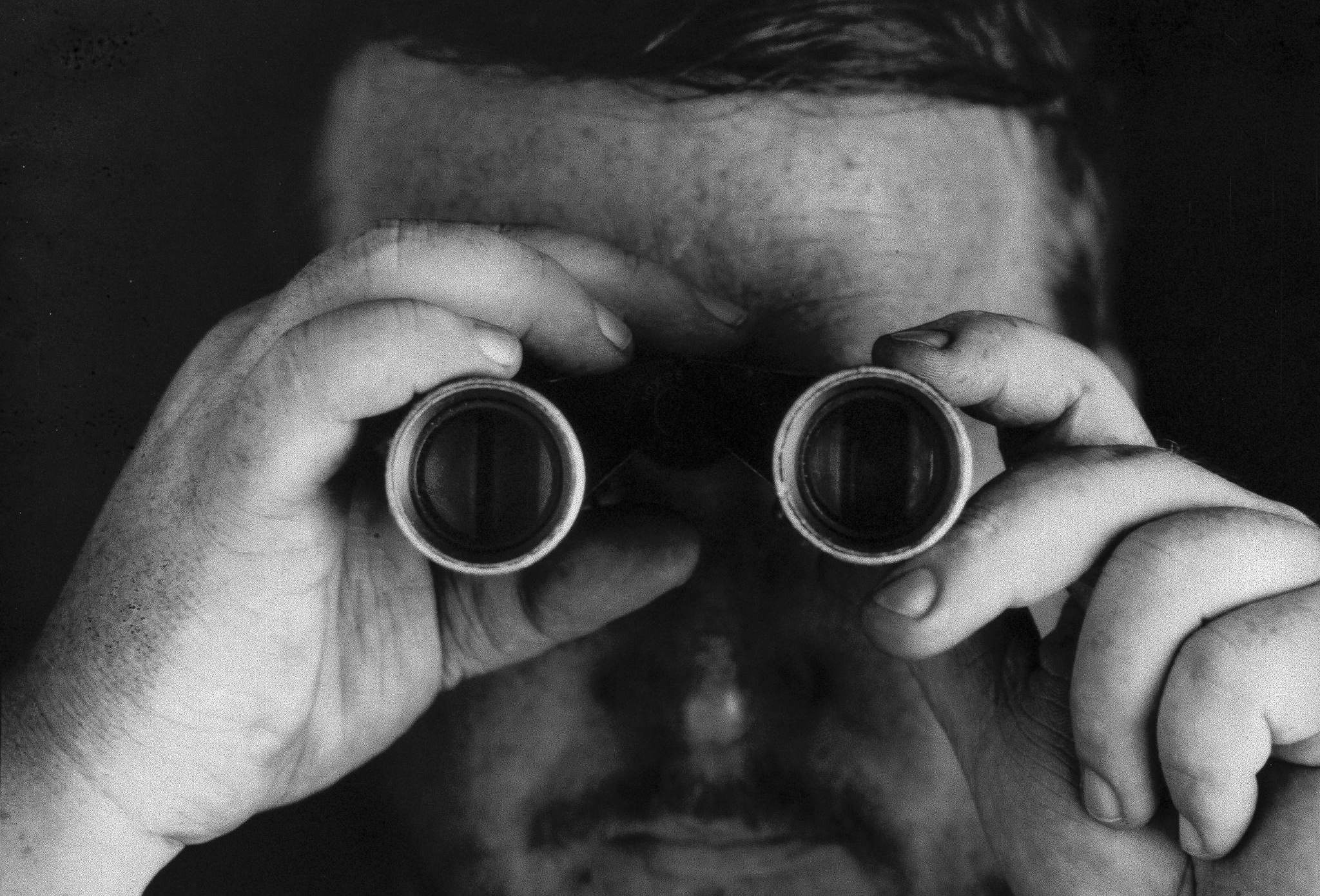

He shattered the myth of privacy in this all digital age and showed us that Moore's law had consequences beyond making new chips. These leaks of once secret documents proved that it was not only theoretically possible to monitor everyone all the time and map every connection they make during the day but that it was actually happening and happening now as you speak and as I type. Enemy of the State was no longer science fiction and we all collectively had our Will Smith moment looking at ourselves in the TV and realizing someone else is watching us. So, No, that IT guy or colleague in the cubicle next door that tapes over their webcam is not just being paranoid, ok maybe a little.

To remind yourself how we got here watch the events unfold in the documentary Citizenfour. While not the best or most riveting film it will provide a more than adequate refresher and also bring much needed context to the current discourse. For it is far too easy it seems to forget how far to the right the debate has shifted. Quite remarkable it is how we have moved from being amazed that in the "land of the free" the government was conducting mass metadata surveillance and directly spying on its citizenry with very limited oversight to now where we accept it as a defacto norm, the new status quo.

Nevertheless, knowledge of these practices as well as the increasing reliance of the tech giants on cloud services that span borders has forced not only the US and governments everywhere to increase their efforts to crack systems but it has also compelled the service providers in reply to up their security to such Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) as well as develop some backbone to resist in areas where there is overreach.

Spies will always spy and governments also must monitor to maintain sufficient security and ensure justice. But it is important that the needs of security are balanced to ensure the freedom and liberties that we seek to protect are in fact being protected from the wrongdoers but also from ourselves and from fear. I don't know what the right balance is that will eventually be decided by consensus but what I do know is that it is better to have the these arguments in the open and not in secret. To change the laws as the people see fit and not for the people to change to fit the written or unwritten law. Remain vigilant and resist when you must.

Nneko Branche.

Nneko Branche.